Two Voices, One Devotion

A Side-by-Side Comparison of the Fuzhou (1932) and Qingdao (1931) Editions of Sheng Lu Shan Gong

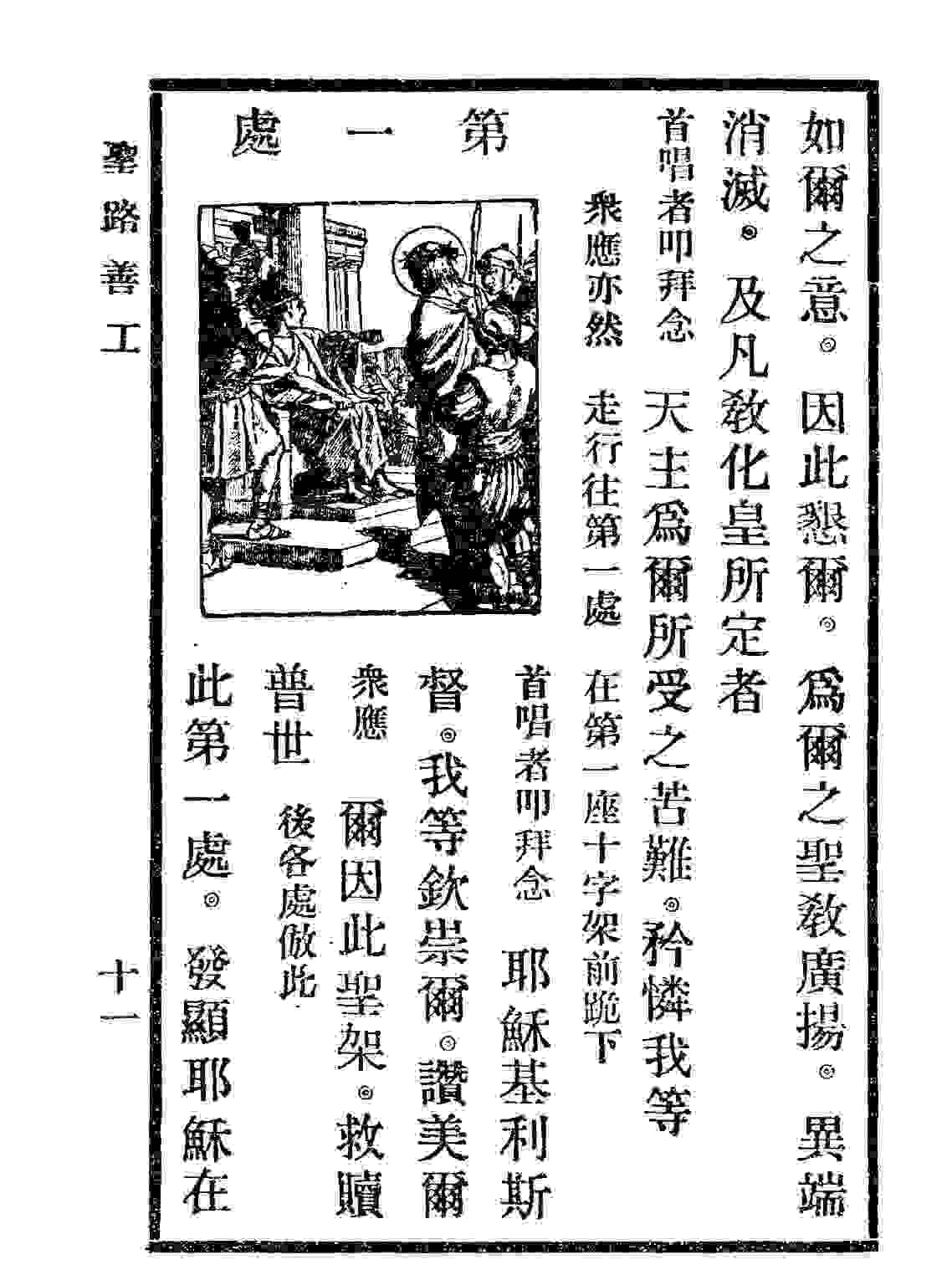

Fuzhou Edition (1932)

Private collection; digital scan produced by the project.

Fuzhou, a historic city on the southeast coast, had been opened to foreign missions since the 19th century. By the 1930s, it was a well-established Catholic stronghold, largely under French missionary leadership (Missions Étrangères de Paris). The city was home to seminaries, girls’ schools, and printing presses that catered to local Catholic communities. Politically, Fuzhou was a quieter provincial capital, somewhat removed from the turbulence of northern China, which gave the Church space to develop devotional life and publications. The 1932 Fuzhou edition of Sheng Lu Shan Gong emerged from this environment: a product of a relatively stable Catholic community, steeped in classical Chinese literary traditions and designed for private prayer and meditation.

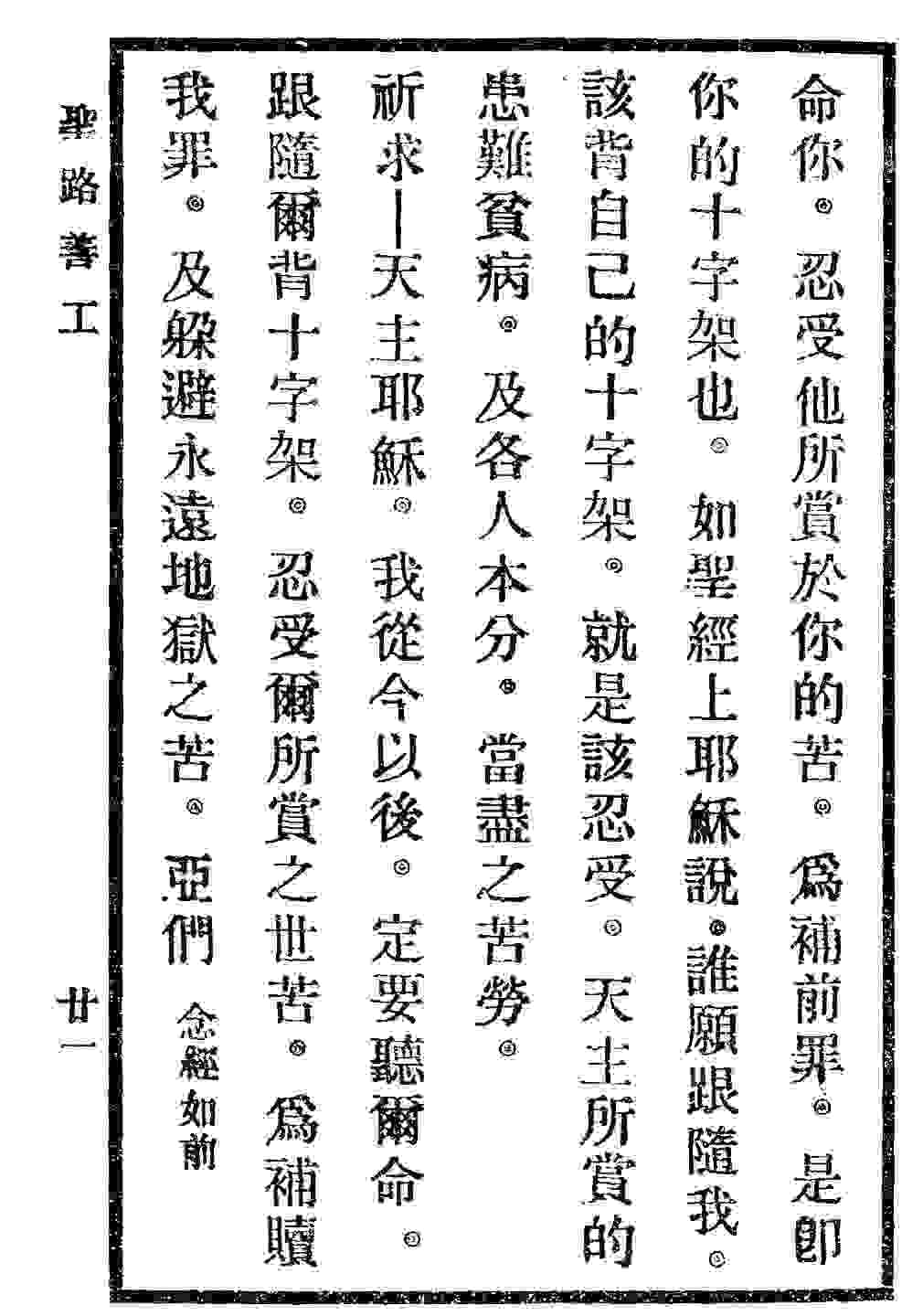

Qingdao Edition (1931)

Wikimedia Commons – Sheng Lu Shan Gong (Qingdao, 1931)

Qingdao, by contrast, was a northern port city with a very different profile. Formerly a German colonial possession (1898–1914), then occupied by Japan, it was returned to Chinese administration in 1922 but retained strong foreign influences. The Catholic Church here was heavily shaped by the Society of the Divine Word (SVD), a German missionary order that maintained schools, seminaries, and a powerful press. Qingdao was cosmopolitan and militarily strategic, marked by rapid modernization and foreign presence. In 1931 — the same year Japan invaded Manchuria — Qingdao remained a politically sensitive city, with its Catholic institutions serving as both spiritual centers and symbols of international ties. The Sheng Lu Shan Gong edition from Qingdao reflects this urban, structured, liturgical culture, intended for public congregational use in a diverse, outward-looking port.

China in the early 1930s was under the Republic of China (Nationalist government), a time of political fragmentation and social change. The Nationalists sought modernization and national unity, but warlordism, Japanese aggression (Manchuria was occupied in 1931), and anti-foreign sentiment shaped the environment. Christianity — Catholic and Protestant — was legally allowed, yet often viewed as tied to foreign powers. Missionary institutions still flourished, operating schools, hospitals, and presses, while the Vatican was beginning to elevate Chinese clergy to leadership. This was a transitional period: a Church between foreign missionary dominance and an emerging Chinese Catholic identity.

The Sheng Lu Shan Gong survives in multiple editions, each shaped by its own historical and regional context. In this section, we turn from background history to a close comparison of the texts themselves, focusing on the 1931 Qingdao edition and the 1932 Fuzhou edition.

Although published just a year apart, these two versions embody distinct voices within Chinese Catholicism. Their differences in language, punctuation, structure, and devotional tone reflect not only the pastoral intentions of their compilers, but also the cultural and political environments in which they were produced.

By analyzing these variations side by side, we can trace how Catholic devotion was adapted for different audiences — from collective, liturgical practice in a cosmopolitan port city to meditative, personal prayer in a provincial capital. The comparison reveals the regional diversity of Chinese Catholic life during the Republican era, and shows how one devotional tradition could take on multiple forms while still echoing the same core faith.

Linguistic Analysis with Direct Quote

Qingdao

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

- Uses more understandable classical Chinese: "耶穌基利斯督" (Jesus Christ)

- full transliteration

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

Simpler sentence structures: "祈求吾主我之天主" ("Pray to our Holy Leader")

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

More direct address: "命你。忍受他所賞於你的苦" ("Commands you. Endure the suffering he gives you")

Linguistic Analysis with Direct Quote

Fuzhou

Fuzhou

More formal theological language: "聖路善工" (Sacred Way Devotion) vs simpler titles

Fuzhou

Complex classical constructions: "因爾所受苦之緣由" ("Because of the reasons for the suffering you endured")

Fuzhou

Elevated liturgical tone: "吾主耶穌蘇見其母親" ("Our Lord Jesus saw his mother")

Translation Philosophy Differences

Qingdao

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

"比辣多定該死之刑" ("Pilate decided the death penalty") - direct, legal terminology

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

"他為救贖人的命令" ("He [gave] commands to redeem people") - straightforward soteriological language

Translation Philosophy Differences

Fuzhou

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

"極重之刑罰痛" ("extremely heavy punishment and pain") - more emotionally intense

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

"聖母瑪利亞我之慈母" ("Holy Mother Mary, my merciful mother") - heightened Marian devotion

Spiritual Content Variations

Christological emphasis

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

"耶穌如今對你說" ("Jesus now says to you") - immediate, personal

Fuzhou

"發顯吾主耶穌蘇" ("Reveals our Lord Jesus") - more liturgically formal

Spiritual Content Variations

Penitential tone:

Qingdao(Earlier printed version)

"你看這樣順命" ("You see this obedience") - focuses on moral example

Fuzhou

"想獸我的靈魂" ("Consider my beastly soul") - more intense self-condemnation

©2025 - CrossEchoes